Funding for Education Transformation: Exploring Power Dynamics in Philanthropy

Co-authored by Hannah Sharp from Big Change and Euan Wilmshurst, with support from Eva Keiffenheim, this article dives deep into trends and untapped potential of global philanthropy and explores how it can support education system transformation.

This article was originally published on Euan Wilmshurst’s LinkedIn page.

In December 2021, as the world emerged from the pandemic, Big Change and others published A New Education Story, to provoke conversation and action for systems change in education. The research identified three drivers for transforming education systems – Purpose (goals and outcomes), Power (voice and agency), and Practice (unlocking innovation). The message was that we won’t do justice to young people by “going back,” to what we consider normal – many of the challenges the pandemic raised were not new for education sectors (Goddard et al., 2021).

Philanthropy can play a significant role in this transformational system change and has the opportunity to shape that role, should it want to. While the norms of traditional philanthropy – short-term, discreet investments through a board of experienced professionals – tend towards sustaining existing systems rather than transforming them into something different, a new way of thinking and doing philanthropy is possible. Many foundations and catalysts like Big Change have flexibility to fund and do things that others can’t or won’t (Saththianathan et al., 2019).

Against the backdrop of philanthropy’s role in education transformation, this article explores the current trends and untapped potential in global philanthropy. Building upon a range of reports and on-the-ground insights from global convenings, we also look at philanthropy through a lens of power. Who has the power in philanthropy and how does it need to shift to transform education so that every young person is set up to thrive and is well-prepared for their futures?

What Is – Current Trends in Global Education Philanthropy

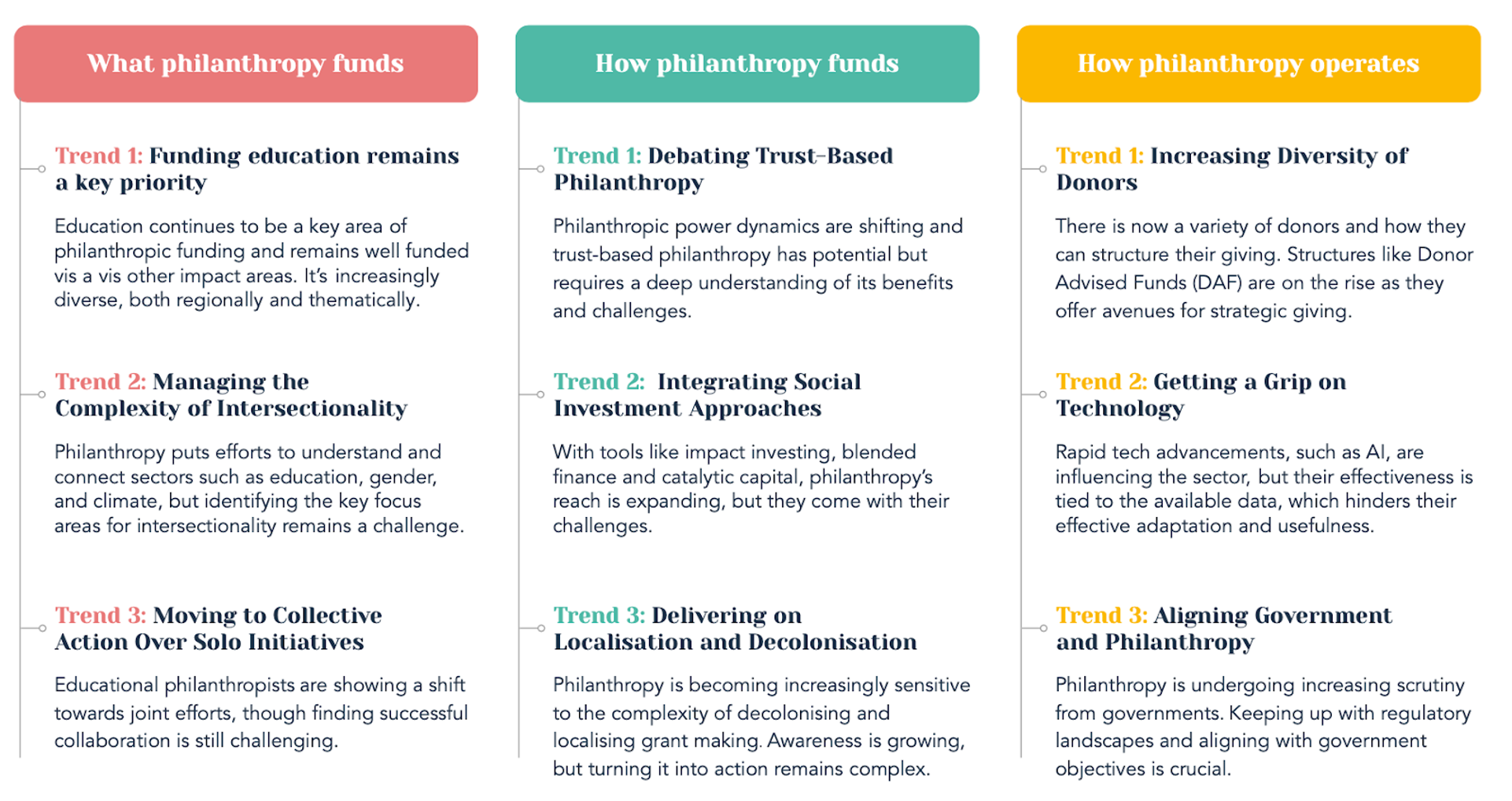

Using both primary data from conversations we had with experts in the field, and secondary research through evidence reviews, a recent report from the International Education Funders Group (IEFG) analyses key trends in three areas of education philanthropy – what it funds, how it funds, and how it operates.

Overall, the philanthropic landscape is evolving in its priorities, methods, and operations, focusing on collaboration, technological integration, and alignment with broader societal goals (McLaughlin & Rickmers, 2023). According to the analysis, education remains a central priority with increasing diversity both regionally and thematically. Still, there’s a challenge in managing the complexities of intersectionality across sectors like education, gender, and climate. On the funding mechanisms, philanthropists are debating trust-based models, integrating social investment tools like impact investing and blended finance, but these approaches come with challenges. Operationally, there’s a rise in donor diversity with structures like Donor Advised Funds gaining traction, technological advancements such as AI influencing the sector, and a growing need for alignment with government objectives and regulations.

In addition to this comprehensive analysis, through conversations at side events around the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and beyond, as well as a look into recent articles, further trends were brought to light.

Connecting Education and Climate

The connection between climate and education is growing stronger. As the climate crisis takes centre stage in global conversations, there is a growing need to understand how the two areas intersect. Funders are significantly influencing this narrative, both on bilateral and multilateral fronts.

Public global education funding and investment are not increasing. With a larger portion of available funds being allocated to climate issues, the challenge arises: how can an education minister tap into this climate funding? This shift in financial priorities emphasises the importance of climate-centric education that equips students with the knowledge and skills they are going to need for a rapidly changing world and climate.

Support for this approach is evident with initiatives like the recent RewirEd Summit hosted by Dubai Cares alongside COP28 UAE helping make the link between climate and education and getting education on the COP agenda for the first time. Other initiatives, such as Teachers for the Planet, highlight the role of educators in the climate discourse and the evolution of climate education.

Challenging the NGO Funding Cycle through Redefining Evidence

From the lens of power – who makes decisions in how we transform systems – who gets funded to change systems is a critical question. Why do international NGOs receive most of the funding? The structure of funding conversations gives them an advantage. Often, big international NGOs have dedicated experts crafting grant proposals showing the effectiveness of their funding use through evidence, securing the same NGOs further funding. The process becomes self-contained, making it challenging to introduce alternative evidence, especially if smaller organisations lack the capacity to provide quantitative data built on expensive longitudinal studies.

While evidence-based decisions are essential, more and more funders are starting to recognise that our current definition of “evidence” is narrow. The process is cyclical: entities that initially receive funds produce the “accepted” evidence, which then attracts even more funding, potentially reducing funders’ willingness to take risks. Conversations are opening up about routes into a broader understanding of evidence – for example by including diverse perspectives and reevaluating who qualifies as an expert on determining effectiveness or influence.

“For organisations with large amounts to disperse, they want to go to the big organisations who have a track record but that is only reinforcing their power. I want them to think about how to shift that more. […] You’re probably not doing systems change unless you’re considering your power in the system, regardless of how much you’re talking about systems change or funding it”

May Miller Dawkins in Philanthropy, systems and change

In the UK, total philanthropic grants to education have remained stagnant over the last five years, with spending on innovation consistently 3-4% of the total (360giving). In an attempt to shift the paradigm, Big Change piloted the Big Education Challenge – a funding initiative to find and back leaders with early-stage bold ideas with the potential to transform education and learning in the UK. Applying Purpose, Power and Practice as drivers for system transformation they changed their approach by seeking early-stage ideas from young people and those with lived experience, and placing a greater emphasis on trust in the way we fund. Taking this approach alone, it will take time to create an evidence base of what’s required to support and develop early-stage ideas, but they are starting to fill a gap and invite others to partner and learn with them to develop innovation funding further.

A Paradigm Shift Towards Localisation in Global Education Funding

In philanthropy, there has been a new resolve to invest more in local communities and locally-led organisations and processes. Previously, there was a willingness to relinquish power, brand, and identity by contributing to pooled funds, but through a more conscious look at power and social justice that sentiment is waning (Bouchie, 2023). This approach prompts a reevaluation of the role of international NGOs.

A key question that came up during last year’s UNGA week was “Why are we supporting them when, considering the localisation discourse, we could directly fund local entities?” A data point that’s reflecting this shift in thinking, is rising investments in funds like the Global Partnership for Education who have mechanisms in countries through their local education groups, which are highly inclusive and highly localised.

What If – Shifting Focus to the Third Horizon and Sharing Power

Based on current trends and insights, many of which are promising, there is still significant untapped potential. The second section of this article offers a provocation for new approaches and actions in global education philanthropy.

“My fear is that people will look back from [2030] and wonder why we did not do more; why we busied ourselves improving broken systems when we needed to make much bigger, bolder commitments to change the world for the better.”

Charles Leadbeater in Philanthropy, systems and change (2018)

What if we applied long-termism in global education philanthropy?

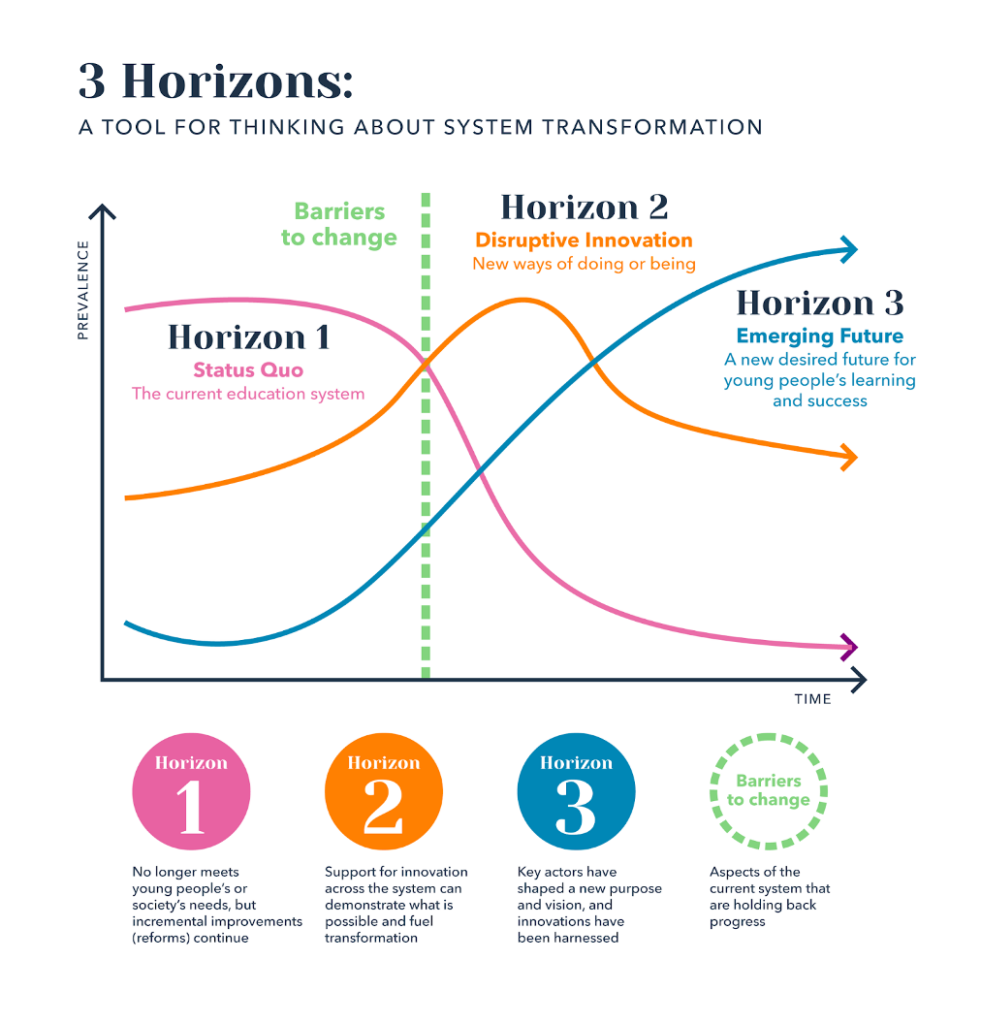

Looking at philanthropy through the lens of the Three Horizons unlocks different activity patterns. In Horizon 1 philanthropists see ‘business as usual’. In Horizon 2= outcome-based funders attempt to innovate but are not willing to take much risk. They are arguably propping up the current system. Horizon 3 includes angel investors, individuals and next-generation philanthropists who are more used to taking risk in the commercial world.

When organisations operate through a 3rd Horizon lens, they know the old ‘business as usual’ systems are going to fail. According to Cassie Robinson from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) , “In most conversations about whether to prop up business as usual and invest in what we know, or to try something different, the 3rd Horizon ‘visionary’ voice gets drowned out.”(Robinson, 2022). While it’s not possible to get to the 3rd Horizon through ‘continuous improvement’, we need both – something to sustain and improve the system whilst other work is focused on the system transition.

A paradigm shift is required to bring out the 3rd Horizon. If funders want to see the 3rd Horizon in funding proposals, new types of questions are needed – questions that include reflection on whether the system is the right system in the first place instead of focusing on ways to improve the existing system.

Robinson suggests funders ask themselves the following questions (Robinson, 2022):

- How is what you’re asking of potential grantees speaking to that 3rd Horizon?

- How are your processes encouraging the third Horizon to express itself?

- Are you willing to let go of being shown something that worked previously? 3rd Horizon work can’t be validated by showing something that has worked previously. It is new. It is different.

- And with your existing grantees, to what extent are you framing your ongoing relationship with them so that the third Horizon can come up in the conversation and stay there long enough to become convincing and practical?

One example that incorporates parts of this is Schools2030 . It is a ten-year participatory learning improvement programme which is looking at schools in 10 countries that received funding from organisations like Oak Foundation, The LEGO Foundation and Aga Khan Foundation with the goal “to equip young people with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values they need to become contributing and thriving members of their societies.”

What if we shifted who has decision-making power in philanthropy?

The 3rd horizon is crucial, but equally important is determining who has the authority to make funding decisions. The recent shift towards localised funding and debates over the evidence needed for substantial funding are part of a bigger debate.

Large philanthropic organisations need to re-evaluate their decision-making processes and criteria for expertise. Currently, there is a significant lack of representation from young people in decision-making roles. Even on a global scale, it is rare to find young individuals serving on the boards of major educational institutions. While some organisations appoint youth ambassadors as advisors, this often doesn’t go beyond superficial, tokenistic engagement. Intergenerational collaboration entails people of different ages sharing power leading to meaningful dialogue, shared decision-making, and collective action. Reconsidering how decisions are made within large institutional philanthropic organisations and who qualifies as an expert is one way to do it.

In terms of power-sharing, an example worth considering is the Community-Centric Fundraising model that is grounded in equity and social justice. The goal is to prioritise the entire community over individual organisations, foster a sense of belonging and interdependence, present work not as individual transactions but holistically, and encourage mutual support between nonprofits.

Another interesting example is Lankelly Chase, a major UK charitable foundation with an endowment of £130m who chose to cease operations due to its increasing discomfort with traditional philanthropy’s ties to colonial and capitalist practices. They aim to distribute their assets in a way that promotes social justice and challenges the traditional power dynamics inherent in large endowments.

Where to Go from Here?

There has never been a better time for philanthropy to step in and make bold moves towards system change. Foundations should explore how their internal workings align with their goals to create the big changes necessary to transform the systems. To bring in the desired changes, there is value in bringing a diversity of voices and experiences into how funding requests are assessed and considered by philanthropy.

To drive impactful change in education philanthropists should consider the following steps:

- Connecting Education and Climate: Reconsider financial priorities towards supporting climate-centric education to equip young people with relevant skills, knowledge, and values for a changing world.

- Challenge the Status Quo: Rethink traditional funding models that may perpetuate existing power dynamics and reevaluate the definition of evidence and how funding requests are processed.

- Support Localisation: Invest more in local communities and locally-led organisations and processes to foster a sense of ownership and empowerment within the communities.

- Embrace Long-Termism: Shift focus towards long-term strategies rather than short-term, discreet investments to allow for sustained efforts towards systemic change in education.

- Shift Decision-Making Power: Reevaluate decision-making processes to include more diverse voices, especially young people and local community representatives, to ensure funding decisions are more inclusive, equitable, and reflective of the communities being served.

This report by The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) is a starting point for foundations to align their ambitions to create big changes. By considering the above recommendations, philanthropists can contribute to meaningful and sustainable transformation in education systems.

“The challenges we face are too great to ignore the power structures, mental models and mindsets that hold problems in place. As institutions, practitioners and funders we are all a part of the story that needs to change.”

Carolyn Curtis, The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI)

About the Authors

This article is a part of the New Education Story Insight Series from Big Change, a UK-based charity acting as a catalyst for change and working in partnership to understand, advocate for, and unlock support for education transformation locally, nationally, and globally. Big Change embraces a “think global, act local” ethos. While actions are focused on supporting transformative education initiatives in the UK, the approach is shaped by global insights. In this spirit, this insight piece brings current trends and potential in education philanthropy to light.

Euan Wilmshurst is a senior adviser with extensive experience across philanthropy, NGOs, and the private sector and runs his own consultancy, KW Strategy , based out of Billund in Denmark. Euan holds a portfolio of advisory and board roles across the global education and early childhood sectors, shaping strategies for a range of global organisations, and serving on the boards of Home-Start UK, STIR Education and Nüdel Kart.

In his previous role as a member of the LEGO Foundation’s executive leadership team, he was responsible for advocacy, partner engagement, and external communications, focusing on the transformative power of learning through play in education and early childhood development.

Euan has twice served on the board of the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) representing the private sector and private philanthropy. He has also been an advisor to the Clinton Global Initiative’s Education Working Group and DFID’s Girls Education Challenge, providing strategic guidance in education policy and development.

His previous experience in senior global roles with organisations such as IBM, CIFF, Pearson, WPP, and The Coca-Cola Company has refined his expertise in integrating philanthropic and educational strategies for broader societal impact.

Hannah Sharp is the Director of Development at Big Change, she works with funders and philanthropists to support Big Change’s role as a catalyst for change in education and learning. With a professional history in philanthropy and fundraising, Hannah has diverse global and local experience working on more traditional philanthropy, charity business partnerships, venture philanthropy and social impact bonds. Prior to Big Change, she was part of the team behind ThinkForward, an award-winning coaching programme bridging education and employment and incubated by Impetus.

References

- Bouchie, S. (2023). Leading to local: How philanthropists can learn to better partner with locally led organisations. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/leading_to_local#

- Butler, P. (2023). UK charity foundation to abolish itself and give away £130m. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/11/uk-charity-foundation-to-abolish-itself-and-give-away-130m

- Goddard, C., Chung, C. K., Keiffenheim, E., & Temperley, J. (2021). A new education story: Three drivers to transform education systems. Big Change. https://bigchange.org/new-education-story

- McLaughlin, C., & Rickmers, D. (2023). What’s next for education philanthropy? Understanding and engaging with philanthropic trends. Heriot Row Advisors; International Education Funders Group. Retrieved from https://iefg.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/What%27s%20Next%20for%20Education%20Philanthropy.pdf

- Robinson, C. (2022, January 23). Funding the third horizon. Retrieved from https://cassierobinson.medium.com/funding-the-third-horizon-ef76a60be9bb

- Saththianathan, A., Fay, C., Curtis, C., Vanstone, C., Freeman, S., & Dusseldorp, T. (2019). Philanthropy, systems and change. TACSI. https://www.tacsi.org.au/file/kl3jo5w1n/TACSI_Philanthropy%20Systems%20and%20Change_2019_report.pdf

- Wilmshurst, E., & Van Horn, J. (2023, October 04). 3 ways philanthropy can help transform education. Global Partnership for Education. Retrieved from https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/3-ways-philanthropy-can-help-transform-education