Transforming Education Through Global Collaboration: The Medellín Challenge Journey

Gloria Mercedes Figueroa Ortiz is a General Director of the San José de Las Vegas School in Colombia. As a Master of Education and Specialist in Pedagogy and Human Management, she has gained experience in the private and public sectors of education. Passionate about education as one of the great solutions for the world’s problems, Gloria is also a visionary of the future of learning through ICT and sustainability to enhance opportunities for students and citizens of the world.

María Paulina Arango Fernández is researcher, educator and program Evaluator with a Ph.D. in International and Multicultural Education and an M.S. in International Affairs. In her career, she has assessed the impact of educational initiatives aimed at improving literacy and maths outcomes for children. María Paulina’s expertise extends to academic coordination and strategic advising, where she shaped pedagogical processes and fostered collaborations with various educational institutions. She has worked as a consultant for organisations involved in transitional justice, youth empowerment, and educational program improvement, drawing on her in-depth knowledge of the Colombian context. María Paulina has authored academic papers and articles on education and conflict resolution and received the United States Institute of Peace Peace Scholar Award for her work.

The Medellín Challenge is an intergenerational initiative developed by San José de Las Vegas School in 2022, to look at local solutions to the kind of challenges the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are designed to address. In 2023 the project expanded to the international arena, working together to design solutions for three specific SDG-related challenges in Medellín. The Medellín Challenge is a school-to-school collaboration operating at a local and international level.

This interview between Gloria Mercedes Figueroa Ortiz, María Paulina Arango Fernández and Eva Keiffenheim is part of the New Education Story series and brings the drivers of education transformation alive in different contexts.

This interview was originally published on Gloria Figueroa’s LinkedIn.

About the Medellín Challenge

Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city, with a population of 2.5 million, faces the coexistence of commerce, industry, health services, and innovation with social inequalities, poverty, exclusions and environmental problems. With the global relevance of the local issues, San José de Las Vegas School designed the Medellín Challenge, recognising the need to prepare students to facilitate inclusion, equity, collective responsibility and intercultural collaboration across generations and borders.

In 2022, STEAM+H (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics and Humanities) learning experiences led to the concept of the Medellín Challenge. The initiative brought students from 12 schools in Medellín and five schools from India, Qatar, Mexico, Spain and the US together, to address three local challenges that are linked to Sustainable Development Goals: high dropout rates related to quality education (SDG4); food insecurity related to reduced inequalities (SDG10); and lack of drinking water linked to clean water (SDG6). To create an effective learning community, the San José de Las Vegas school empowered its students to define the challenge’s focus and purpose and to share academic and administrative responsibilities among them.

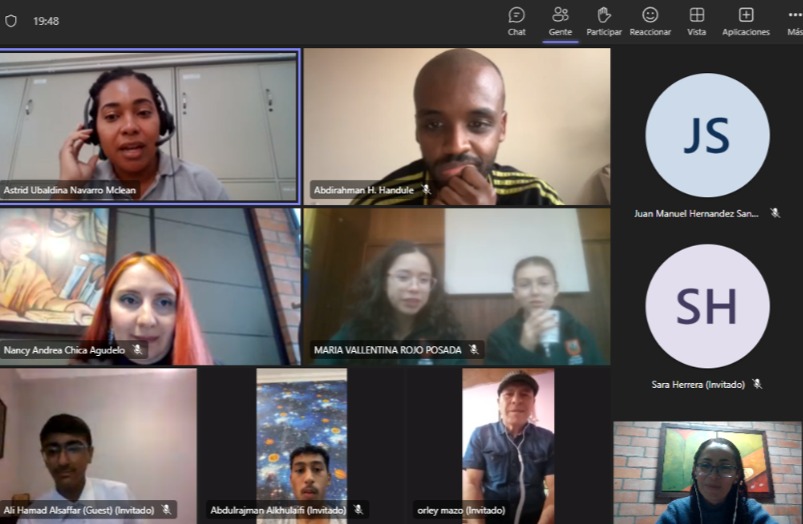

Over four months, students and teachers met online and worked together to find solutions to the city’s issues, assigning roles to its members and defining a working schedule. The school facilitated network and knowledge building by inviting local and international experts to train students and teachers in technological and methodological skills and to provide feedback. This training helped build networks and empathy among participants.

Following the online stage, the teams met in Medellín for one week of face-to-face collaboration. They explored neighbourhoods, interacted with local leaders, sought feedback from industry experts and prototyped their solutions, which they later shared with the groups. The vital part of the Medellín Challenge was in distributing leadership across formal and informal roles, ensuring equitable participation in discussions and decision-making. In this horizontal learning experience, stakeholders’ ideas, skills and knowledge were valued and leveraged to find solutions to the city’s challenges.

This experience expanded education to social spaces, fostering awareness of local and global challenges and a sense of responsibility. It also empowered youth agencies, as students realised that working together could generate social capital, drive positive transformations, develop technological and digital competencies, and build a better world. It also required a switch from traditional hierarchical methods to empower students to lead solutions. Making the Medellín Challenge a reality required building trust with other schools, parents and marginalised communities, prioritising learning opportunities and collaboration.

After the Challenge, the San José de Las Vegas School decided to implement the solutions of two teams to generate a real positive impact in the communities. Local and international students, teachers and school leaders noted that they learned more about Medellín and its community needs, improved connection with different people, learned about interdisciplinarity, applied new technologies, and developed collaboration and solidarity. This challenge demonstrates the potential for learning, unlocking innovation and developing new skills across ages, cultures, and borders.

How has it all started? How do you initiate and navigate change?

Gloria: It started because of COVID when we were reconsidering what we would do if the kids were behind and were not motivated or scared to be at school. I started as the general director just one month before the COVID lockdown, which was a big challenge. But we saw it as an opportunity for learning.

The teachers didn’t know what to do because they didn’t have the chance to work online before COVID. The first day we had an online meeting, I asked them to stay in their offices to show them how to do it. I remember going from office to office, checking if they could get online. My first thoughts were: how do I make them feel comfortable and confident? What is an easy way to empower them? So I talked to my board, and we stopped the school for a week and hired digital experts to be the teachers’ mentors. The teachers were like students, taking their time and learning to be comfortable teaching online. They acknowledged they might make mistakes, but they will be there. A week later, we were ready to bring students back online.

The community evaluated this experience very well. As we already had teachers learning, we decided to bring more opportunities for students to actively participate in the learning. One thing about education that I have always found difficult is changing the curriculum. So we were jointly brainstorming ideas about what we could do differently using the hours of the curriculum, but not in the curriculum. We decided to implement the STEM project so students could think about real problems. In 2021, we started a two-week pilot in three different grades. As a result, the students and families were very active and involved, learning inside the school, and suggesting going out there and analysing real problems in neighbourhoods.

So this is the reason we started it – we wanted the students to be active learners because learning is our main purpose. We see that the students need passion and motivation to continue learning after school. Many are thinking about what to study at university but need to know what they are good at. When students get involved in real problems, they start looking for answers, which makes them feel more passionate, confident, and productive. Inviting people from other countries came up during our conversations with teachers, leaders, and students. And this was when we thought about the Medellín Challenge and inviting others to talk and see our city. We knew we didn’t have a good reputation, but we wanted to show countries with similar situations that we were not alone.

What is the role of intergenerational leadership within that change?

Gloria: The most important thing is to have open opportunities. We don’t tell teachers what to do, we invite them to participate. When we first introduced the two-week STEM project, some teachers were unhappy because they wouldn’t have all the grades they needed for the end of the period. So we decided to start with the teachers who wanted to be a part of it. Then the others began to see it as a good opportunity and that the students enjoyed it. As we were closing the first STEM experience, one of the students said at the end: “I love the experience, but I need to ask you, teachers – can you let us decide later how the problem should be solved?” We didn’t have to tell the teachers what to do, it was the students asking them to let them think. So the teachers started to open up more and listen to students. Both teachers and students are part of the team. For me, the crucial moment was when we decided to switch from teaching to learning. It has been a process, and it hasn’t been easy.

Now that we’ve opened the second edition of the Medellín challenge, almost everybody wants to be there, although it’s at different times of school. They are just passionate about education and finding a different way to learn. The teachers still need to know how to evaluate the moment the students learn and develop competencies. That’s why it is not still in the curriculum itself. The Medellín Challenge is where teachers learn with the students, the experts, the city, and people worldwide. We are going to grow with ideas and solutions the community needs. So the students will apply maths, biology and all the things they have learned while working.

How has your collaborative effort evolved into learning ecosystems?

María Paulina: Before these experiences, we had a very traditional teaching method with different knowledge areas. Now teachers work together and share diverse expertise and knowledge. They started to understand what they are good at and what they don’t know, and that’s okay. They began to reconsider what they evaluate, what are the things that they want the students to learn and understand, not just memorise.

Gloria: And it is amazing how our teachers work with the teachers from other schools. Often, the principals of other schools ask me to send our teachers to their schools so they can talk and exchange knowledge and experience. As other schools are watching, this collaborative leadership is becoming bigger and bigger. We are open to sharing our methodology and talking to other principals and teachers. When other teachers ask me if they can share something, I always say it’s all open. This is not only for one context, city, or country but for all of us learning together. I think the Medellín Challenge can open up a new learning possibility and transform how we administrate education as leaders.

María Paulina: One last thing I’d like to add, we have a cultural advantage in Colombia in that we don’t have a very hierarchical system. So, it’s natural that students and teachers feel connected and close to each other.

What does the purpose of education have to do with this?

María Paulina: The COVID crisis showed us that we need to rethink the purpose of education. We were collectively thinking about what the goal should be. Education must be relevant for the students, and the way to ensure it is to connect what they are learning with what is happening in their communities. We need to help students to be good citizens. It’s not only about local problems; we are all connected, and some of our issues and challenges are shared in other parts of the world. To overcome them, we need to collaborate and bring together people who think differently. We need to talk with community leaders and experts from different fields to find solutions to complex challenges.